Picture Imperfect

Chapter 8

When Aaron had sped off with Herbert to the quarry, he had refused to listen to the girls explain that their research told them unicorns are most attracted to faerie dust. This of course was an impossibility; they might spend as much time seeking out faerie dust as they would seeking out a unicorn. So they wasted away most of the afternoon searching for more information in their home. Thankfully, Mrs. Dolor loved Greek mythology and had a few books dedicated to myths and fables on the family bookshelf next to the old grandfather clock in the living-room.

“This book says they ‘live on top of rainbows’,” Esther read aloud.

“Well, that doesn’t make much sense,” Marian responded. “The one we saw came from a forest.”

“Maybe they just like rainbows. We could always make a rainbow with the garden hose.”

“That’s a silly idea,” Marian playfully replied. “But then again, none of this seems to make much sense, and the boys ran off without us. So we may as well try.”

“I could paint one!” Esther added, cocking her head in a silly fashion.

Marian giggled at her little sister.

“This book mentions they are attracted to crying virgins and sweet fruits.” She glanced at the kitchen.

“What’s a virgin again?”

“Don’t worry about it.” Marian smiled sheepishly. “But I think Mom bought some grapes, and we have the apples from Mr. Mewbourn’s. Let’s use those outside the gate and maybe it will come back.”

Marian scuttled about the kitchen in preparation of the lure; Esther collected her paint supplies upstairs. Mrs. Dolor had already set up a room at the west end of the second floor for the kids to use arts and crafts; Esther dabbed her favorite brush into a cup of water, and then into her most vivid violet. She arched the brush across a white sheet of paper and grinned; the brush dove into a cup of water, rinsed itself clean, and drowned itself into a container of indigo.

While Esther was finishing the world’s best painting of a rainbow, Marian placed a bowl of grapes, apples, and dried fruit at the foot of the poplar; she aimed the garden hose into the sunlight over her head; the light danced through the shower and a beautiful rainbow flashed intermittently before her. The porch door slammed, and Esther was with her; her painting found its perfect spot against the poplar’s trunk and fruit bowl. The two girls felt a sense of familiarity from the night before. It all felt silly, and both were far from confident in its success, but the break from anxiety and tedious work brought them relief.

“I had a dream last night,” Esther said, suddenly introspective. “While we were waiting out here with Herbert and Aaron; I dreamt that three giant trolls were in our house, and they were going to eat us. But one of them was stupid, and the others didn’t like him as much. So you convinced them to eat the stupid troll instead of us.”

“That’s a weird dream,” Marian snickered.

“Yeah,” Esther trailed off. “You are a really good big sister, Marian. You do a good job looking out for Herbert and me.”

Marian blushed.

“I really miss our old home,” Esther continued. “I don’t want a bunch of ugly old trolls to try to eat us.”

“Esther, that’s not going to happen,” Marian consoled.

“How do you know?” Esther fired back, and Marian hadn’t realized until now that tears had filled her sister’s eyes. “There’s Cherokee Devils, and monsters, vampires, and weird men watching us…I hate this town.”

“Ess, it was just a dream.”

“But the rest isn’t. What about Mom and Dad?”

“What do you mean?”

“How could they not listen to us? And school is horrible. And I don’t have any friends.”

Marian bowed her head. “I know,” she replied, because there weren’t anything better to say. The girls held each other and remembered their old home; if they tried hard enough, they could still smell the pine flooring and hear the iron swing-set in the backyard; the walk down the loose gravel road to the corner-store; May and Holly from church; the embrace of Grammy and Papa.

Before long, tears were streaming down their cheeks as they held each other in silent solitude.

Broo-hoha!

The girls heard a rusty, yet beautiful whinny; like the sound of a powerful ruler clearing its throat. They raised their bowed heads, wiped their eyes, and gasped.

Under the arching spray of water, a great stallion stood in the yard, majestic and impossible to believe if it weren’t for their own eyes; its hair was as black as onyx; its mane as white as a summer cloud; at the crest of its head protruded a long marble horn, curled like a perfect ice-cream cone, as if the silver horn had twisted while growing. With all its beauty, nothing compared to the fierce stature and evident power of the animal. It stared at the girls like it were waiting.

“Virgins crying in the woods…” Marian muttered.

“Marian,” Esther whispered. “The picture—the picture!”

Marian’s hands and head shook in dilemma; she shuffled the camera around her waist and switched the thing on. She didn’t want to take her eyes off the thing. Esther kept watch intensely. The camera mechanisms rattled and clicked; the lens automatically extended and focused. Marian held it to her eye and her shivering finger started pressing.

Click. Click. Click.

After three snaps, Marian dropped the camera below her face. Something in her stomach made her feel sick taking so many photos. In a way, it felt wrong; like the moment was meant for her enjoyment and not her record. Somehow remembering the moment later through a photograph, instead of a memory, would only make it less real.

She put the camera down, closed her eyes, took a breath, and opened them again. The unicorn was still there! Brilliant and alive. The three of them stared at one another, letting each holy moment pass over them in wonderful waves of joy and amazement.

The great beast shook its head, and the silver mane fluttered in the breeze; it looked as though it were sad and the children wondered what could make something so beautiful look so distraught.

Suddenly, the unicorn kicked its hind legs wildly and stirred into a gallop around the poplar, kicking mud and dirt into the air.

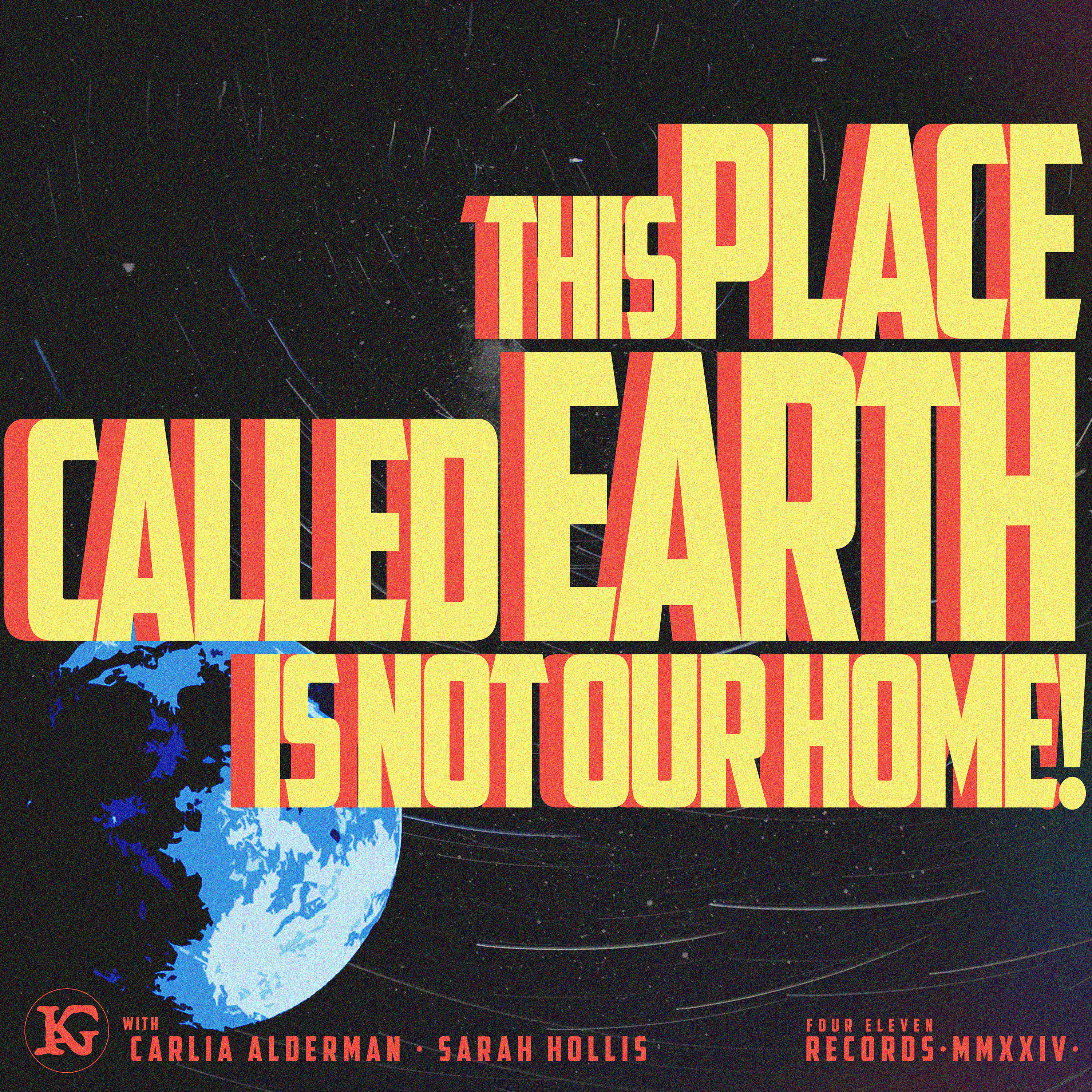

“I take it back, Marian,” Esther whispered. “I do love this place.”

“I didn’t even think this would work,” Marian gasped. “I wish Mom and Dad were here.”

The unicorn stopped running abruptly, and shook its head back and forth. From its soft, sad eyes, it gazed longingly at the girls before rearing up and standing on its hind legs. Its front hooves planted against the poplar—Thud! Then, to the girls’ shock, the beast nailed its horn into the trunk of the tree—Schtuck! It tore its head away from the tree and roared in pain; a piece of the horn had snapped off and stayed behind in the bark.

The unicorn shook its head back and forth, writhing and neighing. With a terrible ferocity and tears streaming from its eyes, the mythical animal burst through the entryway of the gate and disappeared deep into the enchanted forest. The gallop ascended and descended over the mountainside until fading behind the sound of birds and insects singing in the forest.

“Wow,” Marian whispered.

“Let’s see the photo!” Esther exclaimed.

Marian pressed a button on the back of the camera, and a catalogue of saved photos popped up on a small display. She scrolled through photos Mrs. Dolor took while painting, and some more of moving-day. A few of a trip to Abram’s Creek and ice cream downtown. One of Mr. Dolor studying on the couch. Two of Esther and Herbert sleeping on the porch from the night before. And three of blaring white and yellow light.

“Oh no,” Marian said.

“What’s the matter?” Esther asked.

“They are ruined.”

“What?!”

“I forgot to lower the shutter speed after last night,” Marian explained. “There’s nothing here.”

Caught in disbelief, Esther yelled. “There’s nothing we can do?!”

Marian lowered her head. “It’s gone.”

Esther was going to shout in anger, but stopped herself short. “How could—!”

“I’m so stupid.” Marian turned the camera off and pounded her fist on the porch floor.

***

Vinnie the Rat put a recently developed photo on top of his dictionary. Its quality was terrible, and the image looked small and blurry, but you could just make out the image of a black hairy ape strolling across a plank over a small dirty pond in what appeared to be a construction site. Aaron bobbed his head confidently and tried not to make too much eye contact with him.

Vinnie pursed his lips and tapped them with his index finger. He slid a book from under the dictionary on his lap. It was a journal, wrapped in brown worn leather, with a long, thin strip of leather wrapped around it several times.

“As promised,” he said, handing the journal to Aaron. The leather felt soft and pliable, but tough, like ancient things do.

“Thankie, Rat,” Aaron replied.

He left Vinnie’s Grandmother’s porch and approached Herbert, sitting on his bike. Red and black clay was still smeared across his face, under his ears, and over his forearms; the stuff had completely ruined his pants and shoes. He frowned as Aaron saddled his bicycle.

“This feels wrong,” Herbert said.

Aaron laughed. “That’s a-cuz ye’n gots clay in yer butt crack.”

“You know what I mean,” Herbert replied.

“Ye’n wanna get that gap-door a-closed dontcha?” Aaron asked. “What-all he don’t knows ‘on’t hurd ‘em. ’Sides, Vinnie’s had it a-coming to hem.”

Herbert shook his head and kicked his stand up. The boys rode together up the hill in silence.

On the south side of Montvale, Aaron struck up conversation again asking about the creepy man on the hill with Herbert. “What-all’s that-there acorn-cracker a-tawkin’ bout to ye’n on the hill, Herbie?” Aaron asked, balancing the journal in his hand. “—yer ‘secret’?”

“I don’t know,” answered Herbert, shamefaced.

The boys continued mostly in silence to the Dolor house. When they arrived, Herbert went upstairs to wash and change his clothing; Aaron found the girls laying prostrate and miserable in the backyard next to a bowl of uneaten fruit and a soaked painting of a rainbow.

“What-all ‘appen to you twos?” Aaron asked, holding back laughter at the sight.

“Don’t worry about it,” Marian replied grumpily.

“Well, I reckon this’ll chair you-all up.” Aaron smiled and pulled the journal from around his back, shaking it in joyful pleasure.

“You got the picture?!” Esther asked.

“You got the journal!” Marian cheered.

Aaron handed it to Esther. She opened the cover, and a signature in the top corner in pencil read Mewbourn.

“Yeah, well, ’s best ta get back ta ma Paw-Paw, anyhow.”

Marian huddled over Esther’s shoulder. Full of excitement, she didn’t even realize she was removing the book from her little sister’s hands. She flipped the pages and turned it this way and that, reading the old worn letters as best she could. “This is going to take a long time to read through,” she mused. Subconsciously, her legs carried her to the house while her eyes kept scanning through the brown pages.

“‘ey!” Aaron shouted. “I works harder than a peckerwood to git that-there pitcher!” As he was hollering, Herbert, coming fresh from his shower, met Marian at the front door. “Git backs here wit that thang! I wanna seen whats it sez, twos.”

Marian stopped and examined her surprisingly clean brother. She gave Aaron her attention. “What is the matter?”

“The matter’s that I’m a-only body that’s bean ‘roductive! And nows you-all gonna go off with my booty and not e’en a ‘thankie’ fer me.”

Marian smirked at him. “Fine, Aaron,” said she. “Thank you.”

He gave her a dirty look and thought of giving more. “Fergat it!” He threw his arms down. “It don’t e’en matter!”

“What is the matter?” Esther asked.

“Why are you so upset?” Marian added. “I appreciate you helping us. But I need to study this thing if we are going to find any help. If there is any.”

“Yeah, well, good ridden.” Aaron shouted and started to mount his bicycle.

“Is this because of Vinnie?” Herbert asked, a little dumbstruck and lost in the conversation.

“Whut?” Aaron yelled. “Why-all would I keer abouten that?”

“Sometimes, I feel bad when I—”

“Shets up, Herbie!” Aaron yelled. “I smack the ever-livin’ daylights outta—”

“Don’t tell my brother to ‘shut up’!” Esther hollered.

“Everyone shut up!” Marian shouted. “Herbert, what are you talking about?”

“I think he’s mad—” Herbert shouted, and then whispered, “…because he lied.”

The others looked at Aaron; Aaron scowled at Herbert and clenched his jaw.

“Aaron and I didn’t get a photo of the Cherokee Devil—” Herbert continued.

“—Shet up, Herbie!” Aaron exploded.

“We—Aaron staged a photo and gave it to Vinnie,” Herbert explained. “It was all fake. He lied to Vinnie.”

“Why would you do that, Aaron?” Marian asked.

“Do whut?” He mocked, throwing his arms like a clown. “You knowed—you kids are dummern heck. You-all wants this journal so bad, but you ain’t gonna tear the stars outta ‘eaven to gets it. ‘Get the journal’, ‘get the journal’, but whenever I gets it, you start sezzin I no good.”

“You know what you did was wrong!” She shouted. “It’s wrong to steal!”

“So whut?” Aaron yelled back. “I gots what-all we need. Vinnie’s a rat and a idjet.”

“You’re—you’re nothing but a thief! I knew we couldn’t trust you!”

“You knowed whut—Take your stoopid book!” He jerked his handlebars backward).“—I ain’t a hurtin’ for you-all. Good luck fixin’ all thishere on yer own!” He kicked the pedal hard and spun down the slope of their yard into the road and out of sight.

Esther turned to Marian indignantly. “Why did you have to be so mean to him?”

“What?” Marian asked, nonplussed.

“He’s been helping us,” she said. “And the only one who has helped us. And now we are all alone again.” She shoved her way past her sister and brother and went inside.

Marian looked at Herbert. “This isn’t your fault, Herb,” she said.

Herbert looked down, ashamed, considering the broken piece of the wall he still had hidden away in his bedroom, and unsure if it was all his fault. The Top Hat Man surely made him feel that way, and now he knew someone else knew what he had done.

***

The next morning, clouds rolled heavy from the mountains; the valley was gray and lonely. Frigid and piercing, the air cut behind its wet bluster; it made men wear wool hats and wives shake their heads as they scampered from home to automobile on the way to market. The insects nestled in for another month underground. The corn would have to wait longer to be planted. Farmers kicked themselves for moving their tomatoes prematurely.

Down Bell Branch, the intermittent harsh croak of bull frogs broke the collective murmur of next-door chickens who gossiped like busybody old-maids at a cocktail party; their muddy whispers were frequently interrupted by the distant shriek of a heifer in heat and a responding bull on a separate pasture. A cold drizzle, like the damp summers of Vancouver, dropped from leaf to wet branch until a large puddle formed beneath the Dolor’s poplar.

Marian leaned against it and stared at the tree-line; she was only a few thoughts from letting tears fall down her cheeks, but her anger wouldn’t let her. Her brother and sister sat next to her, listening.

“What a waste,” said she, finishing a thought. They had spent much time, effort, and hope in finding this journal of David Crockett, only to be let down by its nonsensical contents. Barely a word in it about the Pardo Stone or whatever Crockett was doing in this forest; much less about why a gate protected an evidently magical piece of land at their property line.

It contained no more than a few words about Juan Pardo’s Stone. In fact, the majority of the book delved into the strange historical accounts of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula; Cherokee and Mayan drawings and loads about something called the Nunnehi and Chaneques. Marian had stayed up the night before, reading the thing from end to end, and only grew more anxious, tired, and angry with each turning page.

She threw the book across the yard and it landed in the mud several feet from her and her siblings.

“Dad didn’t come home last night,” Esther whispered. “I heard Mom tell Grammy on the phone. She sounded worried.”

Herbert kicked the ground. “You know,” said he, looking at each sister intently. “The Ghost said we were supposed to ‘mend’ this.”

“I don’t know what else we can do,” Marian said, shaking her head and staring at the journal across the lawn.

“Maybe we weren’t supposed to try and figure this out on our own,” said Herbert.

“What do you mean?”

Herbert was at a loss for words. “I don’t know.”

“No, I think your right, Herb,” Esther said, leaning up and straightening her shoulders. “We’ve been trying to solve this with other people and learning what we can. But maybe all we needed to do was walk through that gate and find out what happens.”

“The gate with all the monsters?” Marian asked, mockingly. She clenched her jaw and scanned their resolute faces. “Alright,” she conceded half-heartedly. “Let’s see what happens when we go back to the gate. But if I get eaten, I’m blaming both of you.”

The children picked themselves up and brushed the wet dirt from their pants and sneakers. As they crossed the upward grade to the tree line, it occurred to each individually how simple this may have been all along. But if they were honest with themselves, fear kept them from ever approaching the gate again—the fear of monsters, the fear of failure, the fear of guilt and shame, even the fear of being wrong and imagining all of it weighed on their subconscious each night. It felt better to not look again; to try to prove or disprove a way around all of it. But with no other option, the children agreed that the most obvious choice was the one they should have tried first.

As the maple, walnut, and poplar trees came over them, a blue and sweet-smelling haze fell on their shoulders; the air smelled like lavender and honey, and they recalled what this blue smoke brought with it last time.

Before they could utter a word, the Ghost of David Crockett stood before them, looking as if he were leaning against the stone wall, with his knee pulled up, and his hands playing with the coonskin hat on his head.

The children stuttered aghast, but this time were much less afraid of his existence; the month of twists and turns had all but normalized such a thing as a ghost in their backyard.

“Welcome back, children,” said Crockett. “You still look younger than I remember.”

“Have you been here all along?” Marian asked.

“I may ‘ave been, and I may ‘ave not,” said he. “You’ll never know which t’ be true though.” He smirked at the thirteen-year-old. “Now, you ‘re prepared to enter this forest ’t long last. But first, I must ‘ell you why you enter, and ‘ow I came to be in this place. Please, take a seat over their children. Yes, against the sugar maple, and I’ll recount my tale once again.”