Giant Obstacles

Chapter 17

The Lake was the first sound they had heard from the other side of the sugar-berry; but they weren’t incorrect in their estimation of it sounding like someone was swimming. And this, too, was from where the booming thunderous earthquakes had come.

They were the pounding, stolid footsteps of a forty-five-foot-tall man who presently sat upright in the clover field, leaning one elbow on the top of a bent weeping-willow and dipping his free hand into the lake. Suddenly, the children realized the oblong-shaped pickle-puddles they had seen on their trip from the river were the sunken footprints of the giant.

From his terrible gaze and powerful stature, the children felt the pressure one feels next to someone of high importance and grandeur—not the sort of importance that comes with fame or wealth; but character and honor. They knew that he was a man of imperial significance and they would have been tempted to worship him, if they hadn’t innately perceived it would’ve insulted him rather than esteemed him. This pressure resulted in the hardest attempt to keep their eyes up and on him, yet ironically, each felt they mustn’t look away; it was as if they had lived underground for all their lives and finally walked into the sunshine, desiring to look upon the sun’s majesty and bask in its healing power, yet with every glance, brought under enormous pain from its sheer velocity.

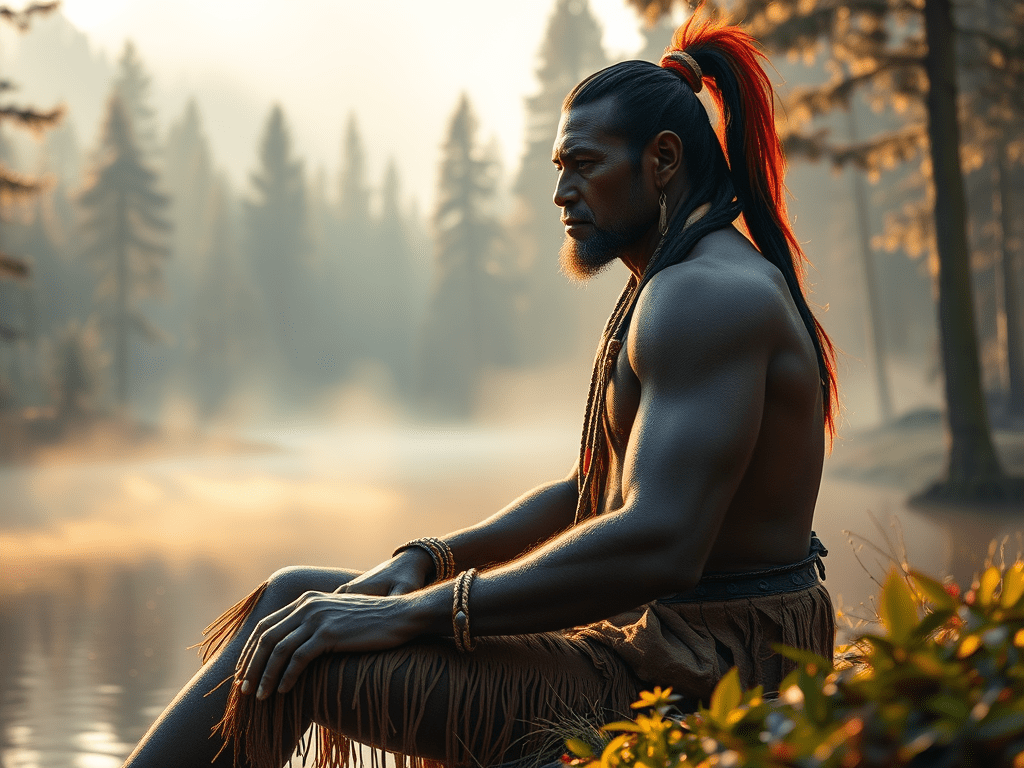

The giant man’s skin was dark olive like an elk; his black hair was tied in a twelve-foot-long crimson ponytail behind his shoulders. He wore only a few strips of tanned leather around his waist and biceps; a necklace of enormous colorful rocks, shells, and stones hung across his bare chest. His free arm draped over his bent knee, and his furrowed brow stared at the children and Donkey whom had just arrived. Around him, the wild animals dawdled, and you had the impression that these black-bear never became aggressive and these deer never grew afraid.

The children were lost for a while in the wonder of the man and his lake. They couldn’t believe how difficult, long, arduous, and dangerous the journey had been, yet suddenly felt as if it were short and easy compared to what they had expected. Deep in their thoughts, they hadn’t realized the giant man was asking them something.

“I’m sorry, sir,” said Marian. “What did you say?”

“Do you know me?” The giant asked again, and Marian felt the hot wind from his breath across the glade.

“I’m sorry, sir,” she replied, “but I don’t think we’ve ever met.”

Aaron and Herbert snickered and shook their heads in disbelief.

The giant leaned back like he was in deep thought. “Long time ago,” he sighed, “everyone knew Maushop.”

Marian stepped into the glade, and the others followed. As they crossed the tall ryegrass, the giant shifted his weight off the willow and lowered his head to examine the teeny children.

They felt his immense eyes rolling over each of them; his extended foot stood upright on its heel, in the middle of the field, seven-feet high. When they crossed under its shadow, Marian’s heart rose to her esophagus and she held her breath. Herbert remembered the last time he had smushed an ant and shivered at the thought. He felt a tug on his shirt and looked to see Starlight fluttering next to him. She was very perturbed and buzzing all about. He couldn’t help but imagine how she must look at him. To her, he was the giant. And this enormous man in the field was a skyscraper. And to the giant, Starlight was smaller than a gnat. “What is it, Starlight?”

The giant’s gaze fell on them like a tower with eyes. Splash! His right arm dumped into the lake, scooped up a handful of water, and splashed his face and ran it through his hair.

“Is that your name? Maushop?” Esther asked, sitting upright on Balaam’s back.

The giant nodded.

“Well, it’s nice to meet you, Maushop,” Marian added, and the others haphazardly agreed.

“I brought the fishes and the whales,” said Maushop. “And gave plenty to the little people. In the morning, they never worried about what they would do by nightfall, because Maushop provided.”

“Guys,” Herbert whispered. “I don’t think Starlight likes this guy very much.” Noya was bounding all around Herbert in a fitful stir, trying to compose herself but finding it very hard not to get angrier and angrier every second.

“Well, what happened to the little people?” asked Marian.

Maushop smiled and looked down at her. “What is your name, little princess?”

“Marian. Marian Dolor.”

“Dolors,” Maushop said to himself. The giant looked up into the mountain range behind them, and the kids wondered if they displeased him.

He looked back at the children. “If the gate is ever broken,” he said, “I protect that which cannot be destroyed.”

“Do you mean the Fountain?” Esther asked.

“Atagahi,” muttered Maushop.

Noya was at wit’s end. She could not contain herself any longer and burst away from Herbert’s shoulder. Her wings took her high into the air where she pulsated her red-orange light at the giant and pointed her finger sternly. The children heard the same buzzing cicada-like sound emanating from her that the Rock Faeries had uttered, and they imagined she was saying very choice words in her faerie language.

It’s been said that giants and fae-folk do not get along very well; something about the faeries’ preternatural love of color, wind and light irritates giants who prefer simple, elemental things like rocks, water, and dirt. Likewise, the fae-folk consider the slow meandering repose of giants as oafish. Nonetheless, giants and fae-folk alike can get along if needed; but what bothered Noya wasn’t brought on by her people’s prejudice, but that this field was once her home, and Maushop’s appearance was what drove her and her kin out of Atagahi.

“Gnats and houseflies,” Maushop swatted his hand at the air in front of him. “Get this thing away from me.”

“Starlight!” Herbert hollered, scared the giant might hurt or even kill her. The giant’s backhand swooped passed the faerie, and its wind blew her toppling head over heels. Her wings caught the air just before she crashed on the ground, and she feverishly retreated to Herbert’s side.

“Careful!” Herbert hollered, but he didn’t know if he was yelling at the faerie or the giant; either of which made him feel abashed for yelling.

“Ugly bright lights and nasty buzzing,” Maushop said to himself. “I miss the ocean.”

“The ocean?” Esther asked. “Is that where you are from?”

“Why ain’tcha head on back they?” Aaron smirked. “We-all can lak after the Founta’n.”

“Maushop lived far away from here, long ago,” said the giant. “I had a wife in the cold places by the ocean. And no—you cannot protect the Lake. Only the artifact can protect it.”

Esther leaned forward on Balaam’s back. She winced when her ankle hit the Donkey’s side. “Where is your wife now?” She asked, clenching her teeth in pain.

“You are in pain, little one,” said Maushop. “Come near to the waters and let them heal you.”

Esther hesitated. Up to this point, all they had wanted to do was reach the fountain on the word of David Crockett; but now, as she had the opportunity to step forward, she was reminded by the long terrible warnings Balaam had told them on their way through the Dead Valley.

She had images pop in her head of ghouls and spirits grabbing her ankle like the Spearfinger, and pulling her into the water, and filling her body with a bogey to haunt her family for the rest of her life.

What if whatever happened to all those Animals that left their homes and never saw their families again happened to her? What if it wasn’t a healing-lake at all, but instead a river like the Lethe, that would make her forget all her loved ones and send her to Hell?

But when she looked up and about; noticing the hopping rabbits, tumbling bear-cubs, and elegant does, her frightful thoughts began to disappear. How could something bad have so much beauty and joy wrapped around it? Esther slid off of Balaam’s back and hobbled on her foot toward the lake. The others, either from the look on Maushop’s face or something in the air, knew they were forbidden to help her unless the giant invited them to do so.

It was a terrifying thing to approach a giant, but Esther found the courage to do it in his sudden kind and gentle face. It took her several quiet minutes, and painful winces, to make it to the water’s edge. But as soon as her toe dipped under the water, and the powerful relief ran up her veins, she shoved the whole foot in, up to her calf. Her skin turned glossy and sleek, as if bathed in oil, and a scent filled the air like violets and shepherd’s purse.

“Oh!” Esther said.

“What’s is it?” Aaron hollered, concerned.

“It feels so cool—I mean, pleasant,” said she.

After only a moment, Esther’s leg felt better than it ever had. She pulled the foot from the water; the wound had vanished. It’s one thing to believe in miracles and another to see one happen. Even as the purple veins wiped away like smeared paint and the wound closed right in front of her like a clam shutting its mouth, she had no idea what to do or think.

She and the others rejoiced at the sight. Maushop smiled with them, yet in a serious, sovereign manner. Esther ran to her siblings and hugged both of them, Aaron, and especially Balaam around his fluffy neck for carrying her so far. She laid down in the grassy field, laughing and twisting her leg, and had a hard time concentrating on anything else for much of their time with Maushop.

After a few minutes of being caught in disbelief and realizing fully the power of this Lake, the children realized they didn’t know what do next, now that they had found the Fountain of Youth. They shuffled their feet awkwardly in the blowing grass and asked each other what they thought, while the giant quietly studied them.

“Why’d Crockett tell us a-come here to shet the gap, onliest find this here big-big giant?” Aaron whispered, letting a bit of his derision seep out. He looked at the giant man and felt his sobering stare wash over him again; he straightened his back and bowed his head.

“Balaam,” said Marian. “Do you know anything?”

“Marian,” replied Balaam. “I wish I knew more, but I only know what I’ve been given. David Crockett ordered me to walk with you. I never knew why.”

“He didn’t tell you what we were doing?” Herbert asked.

“Only that it mattered,” Balaam responded. “And I suppose that was good enough for me. But now that we are in Atagahi, I have many questions that have always befuddled me. One being, why are all these Animals here! I always heard it was a dead place. Mr. Maushop!” Here, he looked at the Giant. “Who are all of these Animals?”

“These that you see are those whom found Atagahi and would not leave it,” said Maushop. “They came to the Lake at the end of their life, and now worry of losing its power. They would rather wait here for the call to cross Atagahi; and thus, they avoid the call to return from it.”

“I heard nothing was across Atagahi,” replied Balaam. “What do you say is across it, then?”

“The Next Page,” replied Maushop. “These Animals do not yet fully understand that once one finds the Lake, the power of the Lake does not remain here. It goes forward with the Animal that returns to the place it came from. But they are not evil in this misunderstanding; only foolish. Even still, it is not such a bad thing to be foolish in paradise.”

“Maushop,” said Marian, finding her confidence behind Balaam’s questions. “We’ve come to find the Fountain of Youth. David Crockett sent us. He told us that we could close the gate if we came here.”

“I know, Dolor children,” he replied. “But I only move for the one who controls the Army of Bones.” The children glanced at one another, confused. “Maybe that’s you one day, but it’s not you today.”

“The Army of Bones? Balaam, do you know what that is?”

“Not a clue,” he replied.

“I don’t understand,”

“I does,” interjected Aaron. “Dagnabit! It mean this here whole stoopid trip—Esther bean begouged, Herbie about fells off a cliff, big ol’ sea-snakes, weaked cankered haints, and ashy faeries!—it were all pointless!”

Maushop’s eyes flared. “Do not despise the day of small things,” he boomed. “It is the Lord’s pleasure to see the work begin. And the little people will begin that work.” His eyes drifted heavenward in a sigh of sorrow. “My little people that are no more.”

“Maushop,” said Marian curiously. “What happened to them?”

“The Wendigo killed them,” he replied short and stern. “And my wife…” His voice trailed. He looked at the lake and submerged his hand under it again, taking a deep breath and restraining his anger; water billowed into the grassy lawn like a rapid. His other hand, forming a fist, raised into the air and fell to the earth beside them, violently; the forest shook, trees rattled, and the birds nearby took to the air, squawking and fleeing. He raised his hand from the earth, leaving behind a crater of rock and dirt. “I’m sorry,” he apologized and quiet sadness rolled over his eyes. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

“Dog me, we-all used to booger’s trine to keel us-alls by now,” Aaron sneered.

“Maushop,” Marian said, “I’m sorry about your wife—”

“Her name was Squannit,” said he.

“Squannit,” Marian repeated. “I’m sorry about Squannit.”

Maushop sighed.

“Hey,” Aaron interjected again. “We-all ‘llowed to sip from that there Fountain of Youth—er—Lake Atagahi or everwhat, and live forevers?” His cocksure attitude generated an angry reproach from Marian. “Whut?” He shrugged.

Maushop smirked at the boy. “Only those in death may enter the Lake.”

“Don’t that take the rag off the bush!” Sneered Aaron. “‘magine gettin’ ta Fountain of Youth, and not a-able to does nothin’ abouten it. We-all finds summen no abody else ever has, and we-all can’t even a-drink from it.”

“Everyone wants eternity,” Maushop said, “But they don’t want to die to receive it.” He raised his submerged hand from the water; a waterfall dumped from his palm and hairy arm. He was pointing.

Across the field was a mysterious rock formation. The group crossed the clover and blowing ryegrass to find a cairn of soapstone; a monument, clearly very old. Wind and rain had sapped the edges round. Herbert imagined even a simple nudge would collapse it.

At its center, a large flat stone revealed the outline of an eight-point star. Noya fluttered down to the shape and ran her little hands through its ridges and crevice. It seemed as though someone had ripped something from the stone much more recently, leaving the mark. Above the carved shape was the remains of a nearly-eroded inscription: “Leave your regrets here to regain life there.”

“What is it?” Esther asked.

“That is the grave of David Crockett,” Maushop called from the other end of the field, and a raven cawed from the tree line. “From it came the artifact. He who controls the artifact, controls the Army of Bones.”

“What does this all this mean?” Herbert asked.

“It means we failed,” said Marian harshly, and the others looked shocked that she was suddenly so despondent. She herself was a little taken aback by her deflated outburst. But all along the conversation with Maushop was a growing sense of failure and regret inside of her; she knew that she had made mistakes on the journey and seeing the glorious giant man seemed to remind her of it every moment.

“Whatever we did, we did it wrong. Maybe it’s because of the cave and Spearfinger. If we went the right way, maybe we would have found the artifact. Or maybe someone got here before us. But all I know is that nothing is happening. David Crockett isn’t here, Maushop won’t help, and whatever this artifact is—sigh—I don’t know.” She dropped her head.

Balaam nudged her with his head. “You have done more in your little life than others will before they are old and die. You have nothing to be ashamed of. Not everything works out how we wished, but at least we tried. And that is something not everyone can say they did.”

Marian smiled and hugged him, and Balaam felt tears on his mane.