The Gate Opens

Chapter 2

“It’s not ours,” answered Marian.

“Whose is it?” replied Esther quickly, eager, like her brother, to see inside the gate. “Why’s it buried behind all these trees in our yard?”

“No one will ever care that we opened it,” added Herbert, shaking with excitement.

“Well,” Marian interjected. “I don’t think it’s right for us to go into someone else’s yard…or property…or whatever this is.”

“It goes to the Smoky Mountains, Marian,” answered Esther. “They belong to everyone!”

“No, they don’t.”

“Well, they should! Anyway, I don’t see any harm in going inside. After all, it’s here in our backyard.”

“Maybe Mom or Dad know—”

“—What are you talking about?” Herbert jumped in. “This is just like Kyle’s grandma’s house at the end of the street in Cocoa. Those old orange groves that we played in. Nobody ever cared, and we made lots of forts inside.”

“That place gave me poison ivy,” Esther mused.

“I’m not saying that it is that place. I’m saying it’s like it.”

“Well, that gate was only as tall as Ess,” said Marian. “I don’t think you are getting over this thing, and I don’t see a handle anywhere.”

Herbert looked over the gate and sighed. His oldest sister was right; the whole thing was solid oak and seamed with iron plates to the brick wall on each side, all of it twice as high as any of them.

Esther stepped closer, close enough to smell the old earth between the wooden beams. She brushed her fingers along the peculiar designs and shapes in the wood. Dirt scraped off between her nails. Marian watched and examined the strange shape with her.

“Looks like a gravestone,” she mused.

“Hmm, no, I think it’s a fountain,” Esther corrected. “Look here at the water spout.”

“Don’t touch it!” Marian warned.

Esther chortled. “Why not? Although,” she whispered to herself, “it does look like this bit of arm or limb is some sort of lever. Hmm. Interesting.”

While the girls examined the worn images closely, Herbert busied himself around the corner of the gate, along the far stretching wall, for another way over. Rhododendron, muscadine, and shrubs covered most of what he saw, but he was sure it led on infinitely. Perhaps if he could climb a tree! But then the idea of getting stuck on the far side frightened him. He banged his fist on the wall. Maybe the shrubbery and eroded brick would hold him.

Ow!

His ankle hit something hard protruding from the base of the wall. Crouching down, he found an oblong stone attached to it, filthy, covered in earth. He rubbed the damp dirt from its angles and blew the soot away. It was a delicate little thing, made of soapstone, about the size of his palm, shaped like the growling face and torso of a cougar. It was a pretty ornament, the sort of trinket that would impress his mother or sisters. But for Herbert, it did nothing more than give him a first step in climbing the wall. He placed his foot on the figurine and lunged upward, grasping and flailing at the vines for support.

Ka-Chink!

Herbert’s foot slipped, and he stumbled to the ground. The figurine had broken from the wall.

“Oh no,” he muttered, crouching down into the ground and grabbing hold of it. He clenched his teeth and hurriedly brushed at the dirt, hoping to find a way to put it back on. After he glanced discreetly to make sure his sisters were still distracted by the door, he sighed heavily and spat on it to wipe the mud off. When he got it clean, he saw the whole backside of the animal was broken apart and splayed open—smashed against some rock when breaking free. A ray of light cut through the dark clouds and canopy to glimmer off the cougar’s emerald eyes, as if to scold him.

While he examined it, he noticed a slight purr resonating from the base of the wall. He leaned close to the hole left by the figurine and felt the faint vibrations of mechanical gears and slipping cylinders snapping into place. Intrigued and confused, he leaned closer, pressing his ear against the hole. The purr soon grew into a violent hum, and he knew soon his sisters would discover him and what he had done. He brushed the dirt from his knees and stuffed the figurine into his belt beneath his shirt.

Ba-boom!

A thunderclap roared from deep within the forest. The wall shook and swayed so violently that the trumpet vine and muscadine lattice fell from it like silly string. A plume of smoke, dirt, and ash erupted from beneath the gate. The children were smothered in a gaseous cloud.

“Oh, my—cough!—goodness!” Esther shouted and backed her hand away from the gate. “What did I—cough! cough!—do?”

Herbert stretched out his arms and stumbled his way back to his sisters in the cloud. “What is going on?” he shouted, shuffling the figurine around to the back of his pants.

“Ess!” Marian shouted. “What—cough!—happened?”

“I don’t know, maybe—cough!—maybe I shouldn’t have touched that little lever. Or—I don’t know.”

Herbert clenched the figurine behind him. “Ess…No, it’s—”

The earth quaked again, led by a cracking, creaking hollow sound like splintering wood and cracking limbs. They stared into the fog aghast as it cleared and revealed that the four-inch thick doors had broken apart and flung wide. Colors of green, violet, marigold, and orange pierced the haze like a rainbow lifting from a waterfall, thick and misty. It traveled skyward, slicing the black clouds above and letting loose the sunset in orange and pink rays.

The children hadn’t a moment to relish its majesty as the earth continued to tremble, albeit less violent as before. A repetitive boom, like the rumble of a locomotive across an open plain, was thubbudy-thubbudy-thubbudying toward the gate, but it was not train nor machine. It was the galloping, quaint hooves of a gallant and pale Little Deer, no taller than Esther, that tore through the gate and reared on its hind legs; a cotton-white hide and shimmering white antlers that sparkled like sunshine on water. Its bleat thundered, and the kids cowered under the weight of its glory. The beast took off north, dashing across their yard, veering slightly out into the street and cutting hard west along Happy Valley Road toward Maryville.

“Oh, my Lord,” said Marian.

“What a cute little deer!” Esther gasped.

But the girls didn’t enjoy the sight of Little Deer’s fading gallop for long. Herbert was tugging at their sides and stammering something inaudible. A deep whine, like that of a bull or whale, erupted from the forest as a large ape-like creature sauntered out of the gate. It cut through the haze, ten-feet-tall, covered in gray and yellow hair, traipsing across the forest. His eyes were slit like a cat’s, but the pupils slanted like offset blades; they blazed as fire at the children.

The beast didn’t make a sound beyond its low whine, but its mere glance convinced them it could speak and comprehend. It dragged behind itself the field-dressed carcass of an elk bull. Backing out of its way, the children let it pass into their backyard. Gracefully, it lifted itself and the carcass onto the low branch of the sweet chestnut and flung to the metal roof over the crest of Herbert’s bedroom.

The children refused to move until, moments later, they heard the thing’s whining howl echo from far away.

“What did we open?” Marian asked.

“Ew! What is this stuff?” Herbert gasped, for a thick fog had spewed out of the gate, very different from the smoke and colorful haze that had filled the air before. It hung low to the ground, only a few inches off of it, and smothered the children’s ankles as it careened down the hill to the southwest. It felt thick and tough against the skin, smooth like oily wax, ready to pull them down if they should slip. A noise clicked in the fog that gave it a life of its own—a mechanical tick-tick-tock. tick-tick-tick-tock.

“It’s an enchanted forest,” Esther thought aloud.

“What do you mean?” Herbert gasped.

“It must be some sort of magical place!”

The children were standing dumbfounded and amazed when an obnoxious cry broke their stupor. “I sees it! I sees it all!” The voice shouted at them from the yard. “I sees what you-all did!”

The Dolors turned to see, to their dismay, Aaron leaning on his bicycle, red hair bouncing this way and that, and pointing—similar to his buffoon dance at school earlier that morning. He dropped his bicycle into the mud and whistled snidely, his face all crooked with a grin as he skipped to the tree line.

“What are you doing here?” Marian asked.

“Is this what you-all do in Flahrida?” he asked, grinning. “Breakin’ open ‘chanted forest gaps that ain’t belong to ye’ns and let loose monsters?”

“Who said it was enchanted?” Marian fired back.

“She just did, briggoty britches,” Aaron gawked, pointing at Esther.

“Yeah, well—who says we broke it open?”

“‘t was prolly good ol’ Herbie who broked it!” Aaron shouted.

“I didn’t do it!” Herbert hollered, checking to make sure his shirt still covered the figurine in his belt loop.

Shriieeee…!

The banshee scream made their blood curdle. It erupted from deep in the forest, echoing out the gate and fading faint into the mountains. The Dolors held hands and froze, too terrified to move, waiting for some new monstrosity to emerge.

“Marian,” Esther whispered. “Something is happening.”

As Aaron crept toward the others, a blue mist displaced the dense, low fog and filled the air around the gate. The children braced themselves. But their fears unnaturally faded. A smell of lavender and honey tinged their nostrils. Their muscles relaxed and they breathed calmly. Fear faded behind wonder, like the sea calls men into mysteries unknown.

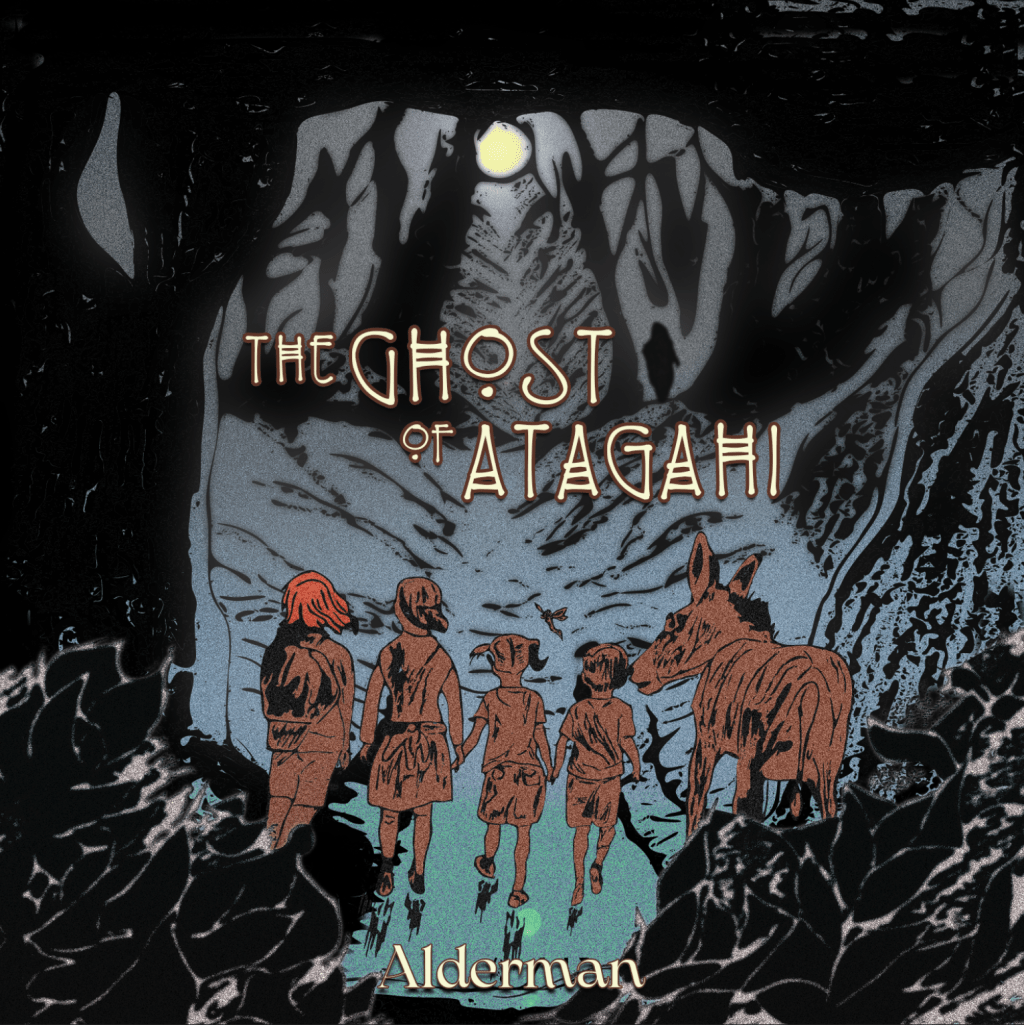

The haze thickened and spun bizarre shapes throughout its cloud, lines and circles, curves and dimples; a translucent image, long and round, crooked and fuzzy, fifteen-feet wide. It came together slowly and sure, until it was right in front of them, and now the common, recognizable shape of a man. But it wasn’t a man at all, at least, he wasn’t whole like a man. The light passed right through him, a blue misty translucence. In fact, he was a Ghost, but not the frightening kind one hears about at Halloween-time; kindness was in his eyes, and gentleness in his smile. The children recognized the faint appearance of deer-skinned garments around him—a leather sack over his shoulder, a long rifle resting in his arm, and a raccoon-skinned hat on his head that trembled in the misty blue breeze.

“Hello children,” the Ghost greeted and dearly shocked them. “You are younger than the last time I saw you.”

Marian broke the children’s gaping stare. “Begging your pardon, sir-Ghost, but we’ve never met you before.”

The Ghost smirked.

“Who are you?” asked Esther.

“I am David Crockett,” said the Ghost. “And you are the children who removed thus little trinket and opened the gates to my forest.”

The Dolor children and Aaron looked at one another in disbelief. Herbert played with the figurine in his pants and shook his head discretely, ashamed.

“I’m sorry if we—” Marian began, before the Ghost interjected.

“No apologies, yet, Marian Dolor,’ interrupted the Ghost and shocking Marian that it knew her name. He looked up and down the steep door and explained. “The gate keeps bay the world’s most vile creatures. And now unto this town, it is open. With said gate insecure, these monsters roam freely. But favor has looked upon you, today, Dolor children.” He removed his coonskin hat and bowed. “The time is come for you to mend such a crisis.”

“David Crockett,” Aaron whispered to himself. “My great-pawpaw knowed arything ‘bout him.”

Marian looked annoyed at the intruder. “Is that supposed to make you an expert?”

“What does he mean ‘mend a crisis’?” Herbert asked.

“I dinst say I ’s an expert, you backlander,” Aaron replied. “I said my great-pawpaw knowed ‘bout him—”

“Stop!” Esther shouted, for while Marian and Aaron were arguing, she noticed the Ghost had disappeared. The kids looked fearfully about the gate and forest threshold, cautious to enter. Marian tried at pushing the door close, but it would not budge even an inch. Oak and walnut were hanging their branches through the clearing, and sunlight fell behind them. The smell of lavender and honey had disappeared.

“Time to go inside,” Marian ordered her younger siblings. “Goodbye, Aaron.”

Herbert and Esther quietly obeyed, following her down the slope toward their home, bewildered and afraid.

Aaron was indignant, though. “Y’ens heared what the Ghost said!” he yelled. “You gots ta shet that gap. Get dem creatures back and that gap closed.”

“He didn’t say that,” Esther replied over her shoulder.

“Why do you care, anyway?” Marian asked.

“Maybes I don’t wanna see my town ever run wit’ wowsers and snawfusses,” Aaron responded. “Maybes it’s nunna you all’s business.”

“You’re right. It is none of our business,” Marian fired back. “The gate isn’t our property, and it’s not like we can do much about it. The thing won’t move. And…and… we are talking about creatures, monsters and ghosts. We are just kids.”

“The little deer was cool,” Herbert added quietly.

“It’s my fault,” Esther groaned.

“What do you mean?” Marian whispered to her.

“I must have done something wrong,” she whispered and shook her head. “Maybe when I was brushing the dirt off of the gate—that little curve in the design. I thought it was a lever. Guys, I think I opened the gate with it.”

Herbert gulped.

“Ess,” Marian said. “It could have been anything why it opened. It’s not our fault this thing is here.”

“You all need ta figger dis out!” Aaron yelled at the group again from the top of the tree line.

“We need to go in for supper!” Marian yelled back as she slammed the door shut behind them.